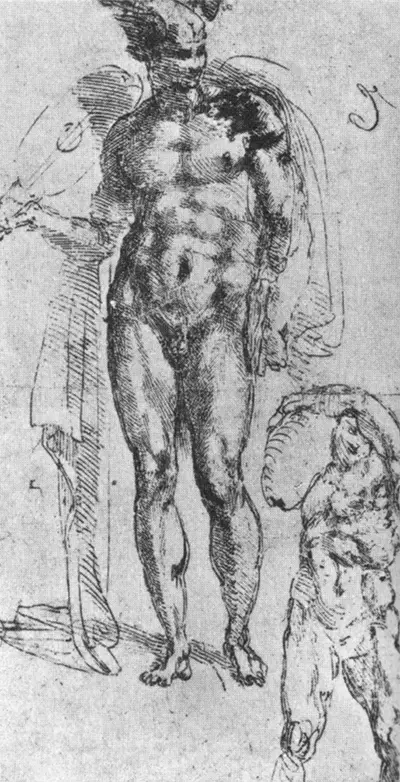

This section draws together all of his major sculptures and provides detailed analysis of each, serving as an excellent reference to the most important medium in which Michelangelo was involved. Sculptor Michelangelo showed ability in this medium from a young age, with Pieta and David being amongst his earliest works. This artist would see a connection between the human form and the soul, carefully studying human anatomy throughout his long, distinguished life. This knowledge would then bring his sculptures to life in a way not seen before at this stage of the Renaissance. There are around 900 study sketches still in existence which underline the lengths that Michelangelo would go to exploring how his finished sculptures might look, even before he commenced the piece.

Michelangelo would use light and shadow to give his sculptures a more lifelike presence, he would also sometimes curve and twist his models together to compliment the overall composition. The growing reputation of this Renaissance master would draw in new commissions across multiple mediums but sculpture was always his preferred tool in demonstrating his genius. It is impossible to underestimate the significance of Michelangelo's legacy as a sculptor. His masterwork David is considered one of the greatest depictions of the human form, showing a technical skill and imaginative symbolism that was (and remains) ground breaking. More than 450 years after he died his work is as highly esteemed and as significant as it was at the time of his death. His style and artistry as a sculptor is still considered the gold standard for other artists to aim for.

This was an artist who would become thought of by some as less of a sculptor or painter, but more as a God. He was even known by some as "the Divine one". He would then become the benchmark against which all later creatives would be compared. It was additionally quite rare for anyone to achieve respect and academic backing within their own lives, something very few in art history have ever managed to achieve. To consider the new ideas and techniques that he brought in, that would normally take time to receive acceptance, but his brilliance could convince others almost overnight. We now consider him to be a part of the start of European art, at least with regards modern civilisation, but in fact at the time he was regarded as the end point - where achievements and abilities had been maximised and nothing after that could ever improve upon it - again giving this image of a divine power who achieved perfection within the art world. Essentially, Michelangelo would take traditional art and re-invent it using his creative mind and innovative techniques.

Whilst representing the final step in this major development in Italian, and later European, art, it is fair to say that he understood and respected the two artists who put together the first two stages in this process - namely Giotto in around 1300, and then Masaccio just over a century later. This three-stage route was explained by Giorgio Vasari in his major examination of Renaissance art which was to become the main source of reference for a number of years. It was also Michelangelo's drawings that would shock those around him because of their beauty and the way in which he had taken the teachings of Domenico Ghirlandaio to extraordinary new lengths. At a young age, it could be seen that he would be the student for only so long, and eventually there would be no one left to tell him anything new. In fact, we do know that he would sit about studying and copying the work of past masters in order to develop his technical ability, making his own versions of pieces from not only Giotto and Masaccio, but also Martin Schongauer, a member of the North Renaissance, some of whose engravings were under the ownership of Michelangelo himself.

Michelangelo was such a master of the Italian Renaissance that he is renowned as a painter, sculptor and architect. He regarded himself first and foremost as a sculptor though, and with David and Pieta amongst his sculptural masterpieces it is easy to understand why. It is extraordinary that even today, many centuries later, he is still regarded as one of the true Renaissance masters and amongst the top ten artists of all time, even though so many other great names have appeared in the years since. It is hard to see that changing anytime soon and the frequent exhibitions and publications around his life and work will help to keep it that way. With most of his works in major public collections, we are also able to see most of them too.

The Philosophy of Michelangelo the Sculptor

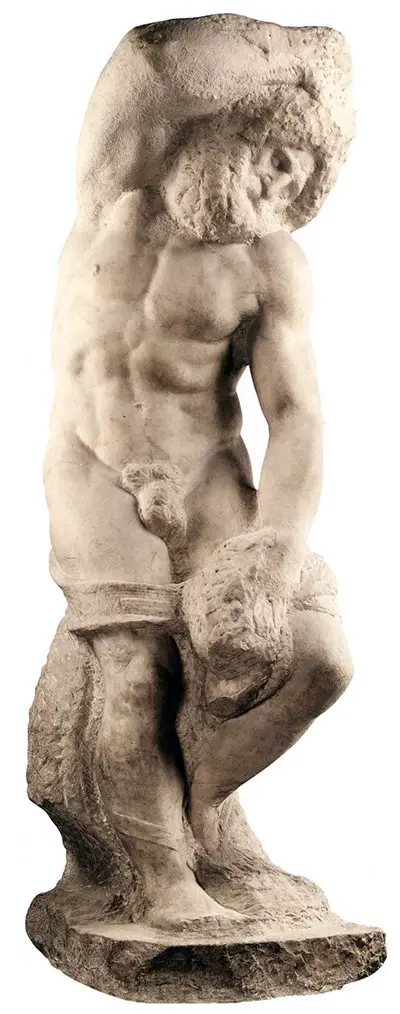

Michelangelo saw sculpture as the art of taking away from something rather than adding to it (as painting adds to a blank canvas) - in essence he was trying to bring into existence the form beneath the stone block in front of him. To do this he produced detailed sketches, but his own spiritual passion within him and his own desire to bring to life the beauty of marble were the driving forces of his talent. There are interesting parallels between the two which could explain his desire for both. The divine eternal life that he sought on earth was created most closely on the eternal marble that he carved.

Early Sculptural Work

Michelangelo was introduced to sculpture whilst studying in the household of the Medici. He began to work almost immediately, producing the 'Madonna of the Steps' between 1490-1492 and 'Battle of the Centaurs' between 1491-1492. These early works - Michelangelo was aged around 15 in 1490 - are indicative of his promise and talent. The Madonna of the Steps is a shallow relief and is his earliest known sculptural work. It is in part a homage to similar work by Donatello, but it showcases Michelangelo's early talent.

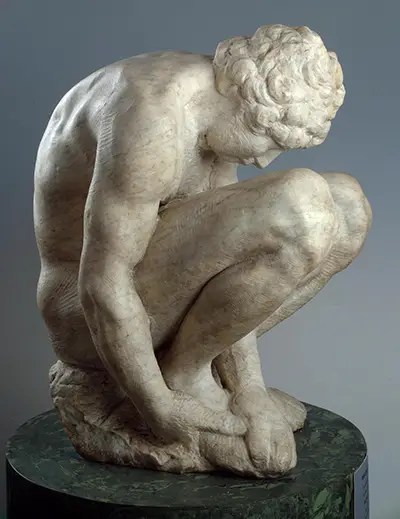

The carving is detailed and delicate, depicting Mary as a loving a protective mother. Battle of the Centaurs was not subject matter of Michelangelo's choosing, but it showcases his ingenuity and innovation as an artist. Here he ignored the practice of the day, instead working multi-dimensionally. It remains unfinished, yet Michelangelo considered it the best of his early works and a keen reminder of why he needed to concentrate on sculpture.

Masterworks: David and Pieta

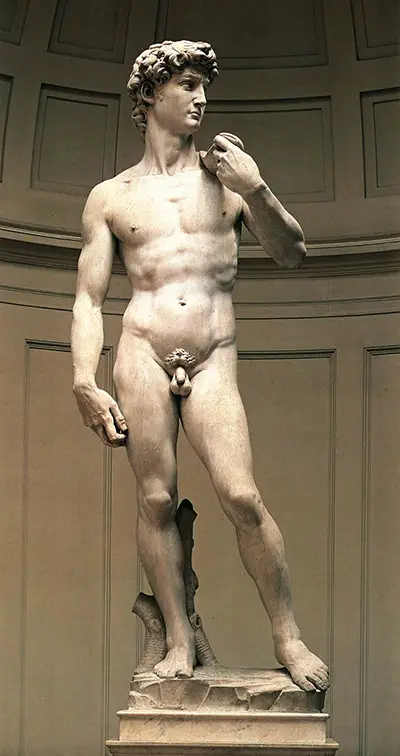

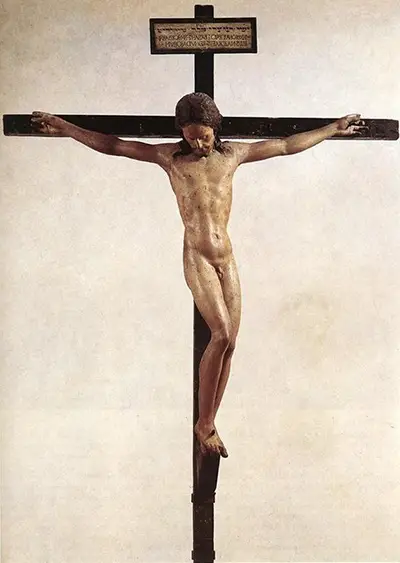

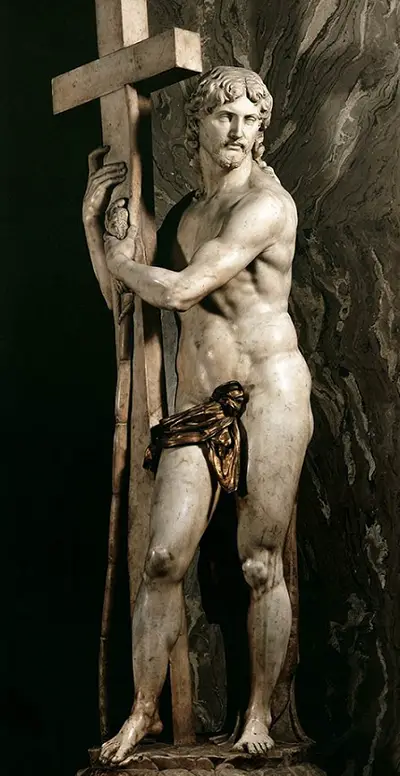

Michelangelo's prodigious talent was evidenced at a young age, so it is no surprise that during his twenties he produced two of the sculptures for which he is most famous: 'Pieta' and 'David'. 'Pieta' was completed in 1499 and was immediately hailed as a masterpiece. The life and emotion that Michelangelo had proved himself capable of bringing to an empty block of stone was clear in the face of the grieving mother holding up her dead son. Pieta established his reputation and as a result he was offered more commissions. One of these was the completion of a project to depict David as a metaphor for Florentine freedom.

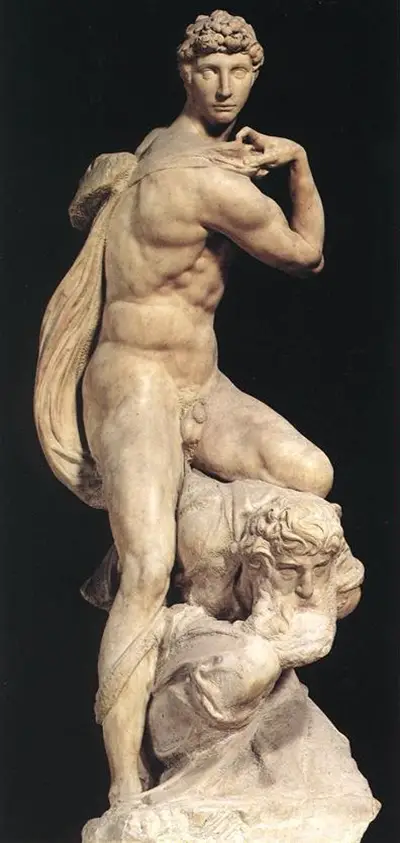

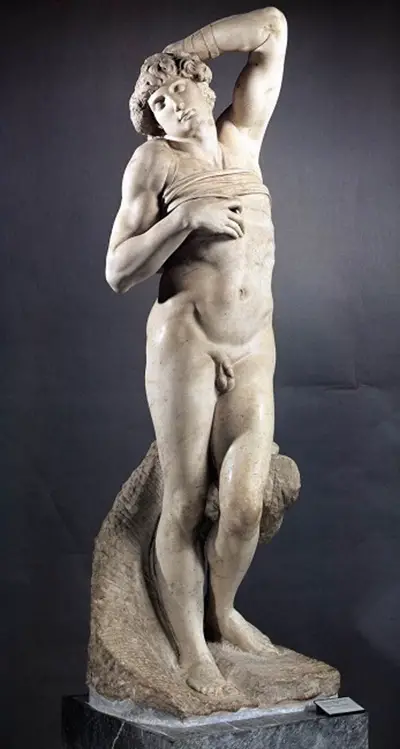

The result immediately solidified his reputation as a sculptor of skill and technical perfection. David also represents Michelangelo's skill at dealing with the male figure. He did this many times in his work, from Bacchus (1496-97) to The Captives Series and beyond, Michelangelo brought to life men who were sturdy and muscular, imbibed with energy and dynamism. His work was classically inspired, but Michelangelo made it multidimensional, meaning that it could (and should) be viewed from any angle.

Michelangelo: Later Years

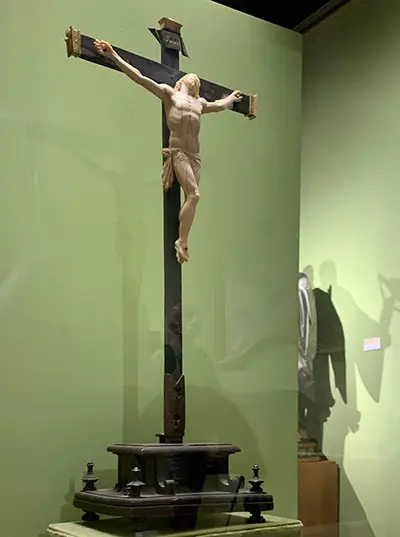

In later years Michelangelo undertook many Pieta which (like the 1498-99 one) depicted the dead Christ in the arms of the Virgin Mary. These are in essence an examination of mortality and explore the sculptor's own reflections on the subject. Most interesting is Pieta Firenze or The Deposition (1550-1561). This depicts Michelangelo himself as Nicodemus, lifting Jesus into the arms of Mary Magdalene and the Virgin Mary.

This is fascinating on two levels. First of all there is the message of the artist as a participant in the suffering of the Christ and acting as a conduit between the divine and the mortal. Secondly there is the process that it represents. As he got older Michelangelo became more of a perfectionist, and this pieta is more than unfinished- Michelangelo smashed the work in part due to being unable to sculpt exactly as he wanted to.

David Sculpture

David, pictured on the right of this page, is a sculpture which is the highlight of Michelangelo's career and came surprisingly early in his life, with it looking as if it was produced by a highly experienced sculptor. The David sculpture was a huge piece, and can thankfully still be appreciated by fans of the artist if they are willing to travel to Italy to see it in all it's glory. There have also been some travelling exhibitions which have displayed accurate reproductions of the original sculpture, and this can be a reasonable alternative for the many who are unable to travel to Italy specifically to see this masterpiece. Discover far more on this piece of Renaissance history on the specific David page.

Pieta Sculpture

Pieta was a notable sculpture from his career and again continues on the religious theme which was so common in commissions during the Renaissance era. The commission for Pieta came from France and allowed Michelangelo the opportunity to go in a slightly different artistic direction for this sculpture, more in line with French styles than Italian. One interesting aspects of this Pieta sculpture is the way in which Mary was portrayed by Michelangelo as being particularly young, certainly in relation to Christ, whom she holds in her arms.

Michelangelo also produced three other sculptures which were very much related with this one, namely The Deposition, Rondanini Pieta and also Palestrina Pieta. This sculpture is now on show at St Peter's Basilica in Vatican City, and is well worth a visit. This was not actually the intended purpose for the piece, but several factors which arose after Michelangelo's death have led to it being moved to this more accessible spot.

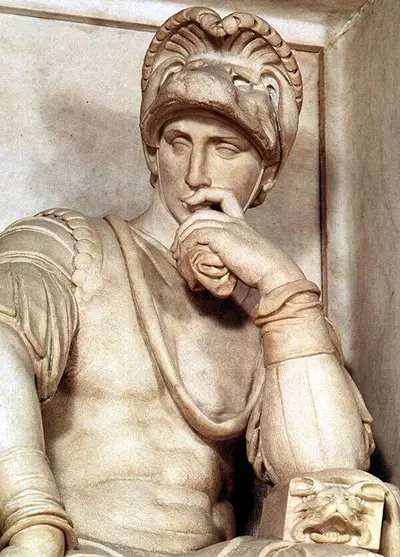

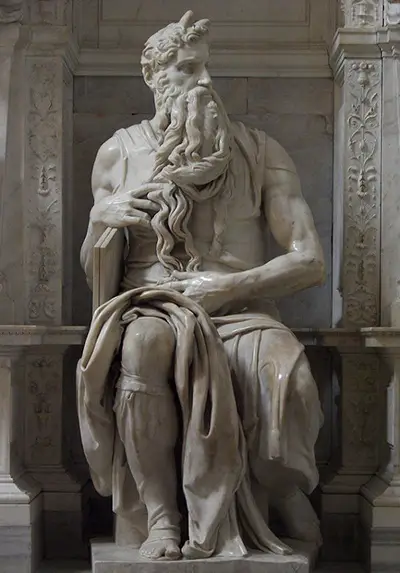

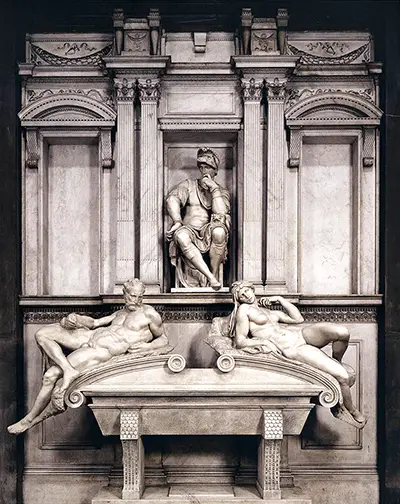

Moses Sculpture

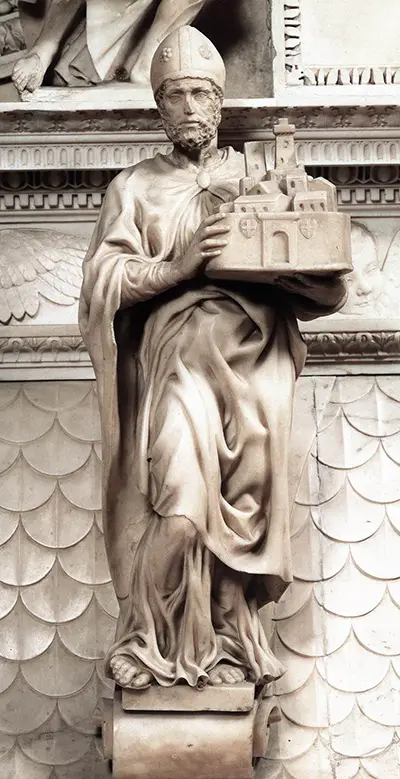

Moses is a full length sculpture which took around two years to complete. This marble artwork stands at an impressive 235cm and remains one of the key works produced by Michelangelo during his career. The church of San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome holds this large sculpture and depicts the biblical figure Moses, as suggested by the title. The strength of character attributed to Moses is captured perfectly by master Michelangelo and the artist took on some technically more-tricky methods in order to get the finish that he most wanted.

The photo to the right is one of favourite photographs of the original, capturing several of the key aspects of this particular sculpture. The Moses sculpture was a key focal point of a larger design produced by Michelangelo for Pope Julius II. It was to be his tomb, and the artist matched the importance of the Pope with an extravagant series of around 40 sculptures to celebrate the life of this key religious icon. Each individual piece in this design deserve their own specific recognition, though, such was the qualities of their creator.

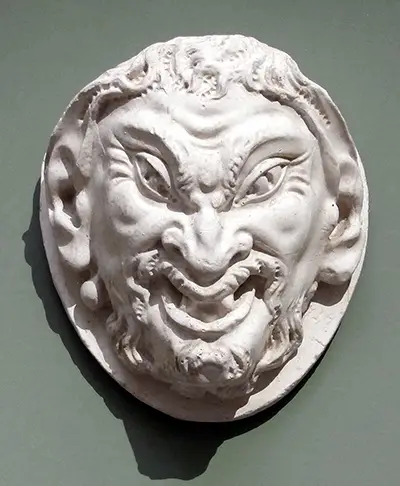

Brutus Sculpture

Michelangelo completed his Brutus bust in 1538, and you can now see the original in the Bargello Florentine Museum. The city itself remains the best place to learn more about the great master, though the Vatican City also retains some of the highlights of his career. This particular piece is important due to the fact that it is believed to be the only bust produced by Michelangelo during his career, despite him being so prolific as a sculptor. Michelangelo used this piece to comment politically on the progress of his beloved Florence and he worked hard to capture strong emotions on the face of his historic subject.

This artist was someone who had great passion and confidence in his work and his position as a respected artist, to the point where he would frequently use his art to communicate messages about how he saw the world. It was not only the art, but also the position in which it was displayed which would convey Michelangelo's message to the world, though the masses may have often missed the meanings behind his sculptures.

Bacchus Sculpture

Bacchus featured here has a dazed look in his face, which clearly has something to do with the bowl of wine which he carries around with him. This sculpture is now on display at the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, and stands at an impressive two metres in height. Whilst the sculpture portrays Bacchus as drunk it is important to remember that he was in fact the God of wine. This particular piece was completed in 1497 and represents one of the better sculptures from the artist's early days. The photograph to the right captures the detail of Bacchus' face with his loose grip on the small bowl of wine.

Michelangelo.jpg)

Michelangelo.jpg)

Michelangelo.jpg)

Michelangelo.jpg)